WSET Diploma: the Quality Assessment

Everyone’s least favorite part of the tasting paper is the quality assessment. It takes the longest to write out, and it’s not as fun as picking out the aromas and flavors or guessing the wine, but it’s worth 25% of the points on your tasting paper.

From just my anecdotal classroom observations, it seems to me that people who struggle with the quality assessment fall into one or two of the following three categories:

They repeat the BLIC according to strict formula in accordance with their Level 3 routine without describing the nuances of the wine and have difficulty explaining their reasons (e.g., “the wine’s acidity and sweetness are in balance, the length is long and the wine’s aromas are complex and intense. Therefore, the wine is outstanding”);

They go the complete opposite direction from #1 above and start waxing poetic about the wine as if they are selling the wine to a customer; and/or

They do not put the time into practicing writing full quality assessments before the exams.

You are not being asked to sell the wine to a customer

The best piece of Diploma advice I ever received was when I took my D4 Sparkling Wine tasting tutorial with Caroline Hermann MW through Capital Wine School, and she said, “Examiners want to know that you know how to write a professional wine review.”

Notice that Caroline didn’t say, “Examiners want to know that you can write the back label of a wine.” You are not here to sell the wine; you are here to sell your conclusion of the wine as a good/very good/outstanding wine drawing from your sensory observations.

You can use words conveying admiration or respect for the wine in front of you, but for any wine other than an “outstanding” wine, you should clearly state the drawbacks keeping the wine from being an outstanding wine with the eye of a professional critic.

How I BLIC

BLIC is the cornerstone of the quality assessment. However, the challenge for Diploma students is explaining the “why” or the “how”. A chief complaint in the examiners’ reports on the tasting exams seems to be that candidates just state that the wine is “in balance” or “has complexity” without explaining why it is in balance or what makes the wine complex. Here is how I think about using BLIC when writing my quality assessments:

Balance

I consider balance to be the most basic characteristic of a good or very good wine because a lot of the characteristics that are considered for balance are measurable and somewhat controllable for a producer. What are the factors that I weigh against each other?

Alcohol/acidity/tannins against the concentration of fruit and other flavors

In wines with residual sugar, sweetness against acidity

In wines with residual sugar, sweetness against the concentration of flavors

In certain styles of wine, certain elements are key factors, so I always address them in my quality assessment. With fortified wines, alcohol is a key factor, so I always address the balance of the alcohol against the concentration of the flavors. With sparkling wines and wines with residual sugar, acidity is a key factor that I always address in my quality assessment.

In addition to the factors above, to the extent that secondary or tertiary characteristics are present in the wine in front of me, I also weigh the primary, secondary and/or tertiary characteristics of the wine against each other. You know when you have a heavily oaked, buttery California Chardonnay and the the oak and butter are the only things you can smell or taste? I consider that to be the result of a lack of balance between the primary fruit and secondary winemaking features. For a wine that is “too old; past its prime,” in my quality assessment, I consider whether the tertiary aromas dominate the wine such that the primary aromas are overpowered and cause the wine to lack freshness, and therefore be unbalanced.

Intensity/Concentration

This one seems ostensibly easy and straightforward - If the intensity of the aromas is “pronounced,” the wine is intense, if the intensity is “light,” it is not. However, I feel like this one needs a little more consideration beyond whether the aromas and flavors jump out at you from the glass. Some of the finest wines may not be as in-your-face in terms of aromas and flavors, but such wines may be considered outstanding due to the finesse and delicacy of the flavors. A good example is comparing a very good non-vintage Champagne that is quite upfront in its aromas and flavors against an outstanding vintage Champagne that has more subtle and elegant aromas.

Note: I tend to give “concentration” a lot of weight when it comes to fortified wines. Fortified wines are generally made in set styles with the usual expected aromas and flavors, and many of the methods of producing fortified wine (e.g., ageing Sherry in the solera system or ageing Vin Doux Naturels in demi-johns over long periods of time) are deployed with the specific intention of increasing the concentration (and complexity) of the flavors in the final wine. As a result, a Sherry aged for the bare minimum of time required by law will be much less concentrated than a 20-year Sherry.

Length/Finish

I consider length/finish to be the single most important factor distinguishing a very good wine from an outstanding wine because most wines do not have a truly long finish. Yes, I still count the number of seconds in a wine’s finish, and I consider around 15 seconds to be a “long” length for me, but I use this just as a general guidepost and not as a hard-and-fast rule. In addition to the length of time, I also consider whether the flavors unfold or evolve on the palate. In my experience, many outstanding wines will often start out with a few flavors that evolve into other flavors on the palate. It’s intriguing and captivating, and I consider it to be the marker of an outstanding wine.

Remember: It is the length of time that the fruit and other positive flavors linger on the palate, not just the length of time that the sensations of acidity, tannins or bitterness stay on your palate.

Complexity

This factor is pretty straightforward. If you have tons of different aromas that are flowing from your pen as you sit down with the wine, the wine will obviously be complex. If you are not really getting much from the wine, it will be “simple.”

I do not subscribe to the concept that if you have flavors or aromas from multiple categories, the wine is “complex.” For example, certain fortified wines, such as Fino Sherry, will have bread dough, apple and hay aromas, which should indicate complexity according to the formula above. However, if there are not additional flavors beyond the typical flavors one would expect to see for that type of wine, I do not consider the wine to be complex.

Go beyond BLIC to consider the nuances of wine

The basic formula in L3 for quality is that if a wine has 2 out of the 4 BLIC characteristics, it is a good wine. If it has 3 out of the 4, it is a very good wine, and if it has 4 out of the 4 characteristics, the wine is outstanding.

However, wine is not as simple as just a mathematical calculation, and Diploma students will often say, “Objectively, the wine has these BLIC characteristics, but I just don’t feel like it is an outstanding wine.” I see this comment particularly with naturally aromatic varietal wines (e.g., Langhe Nebbiolo, New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc). The problem is that we need to stay analytical (it is still called the “systematic approach to tasting”), and we cannot base our quality assessments on just our feelings.

I think it is helpful to start by asking yourself what the objective of the quality assessment on the Diploma tasting exam is and how you can demonstrate that you have met that objective. With Level 3, I would say that the objective is to demonstrate that you have the sensory skills to pick up the aromas, flavors and structural characteristics of a wine and to be able to discern the basics of balance, intensity, length and complexity. At the Diploma level, I would say that the objective is to display not only a mastery of BLIC but also an understanding of the nuances of wine. As a result, I always consider the following “soft” characteristics of the wine - the subtleties that put fine wine on the same pedestal as fine art instead of relegating wine to just a commodity:

Specificity of flavors

Integration of flavors and structural components

Tension

Potential for ageing

Typicity

Texture

Purity of flavors

Not all of the characteristics above will be relevant to the determination of the quality of wine, and the list above is not the exhaustive list of “soft” characteristics to consider. However, the one factor I do consider for all wines is specificity. Outstanding wines have aromas that are specific and personal to that wine (e.g., “lemon curd” versus “lemon”). Acceptable or good wines usually have generic or indistinguishable aromas.

In addition, for certain types of wine, such as sparkling wines and fortified wines, I think that there are certain key characteristics that should always be discussed in the quality assessment. Bubbles are a key characteristic of sparkling wines, so I do think that everyone should comment on them. Are they large, small, creamy, harsh, short-lived or persistent? For fortified wines, alcohol is a key characteristic, so I always comment on the nature of the alcohol - Is it burning, warming, harsh, seamless, well-integrated or astringent?

A lot of people will say, “Can we say this word [xxxxx] to describe the [alcohol][bubbles][tannins]?” My personal perspective is that as long as you choose words that convey clearly to the examiner what you mean and how you feel that it contributes to or detracts from the wine (negatively or positively), then you can use whichever words you want, and you should not get hung up on the exact verbiage.

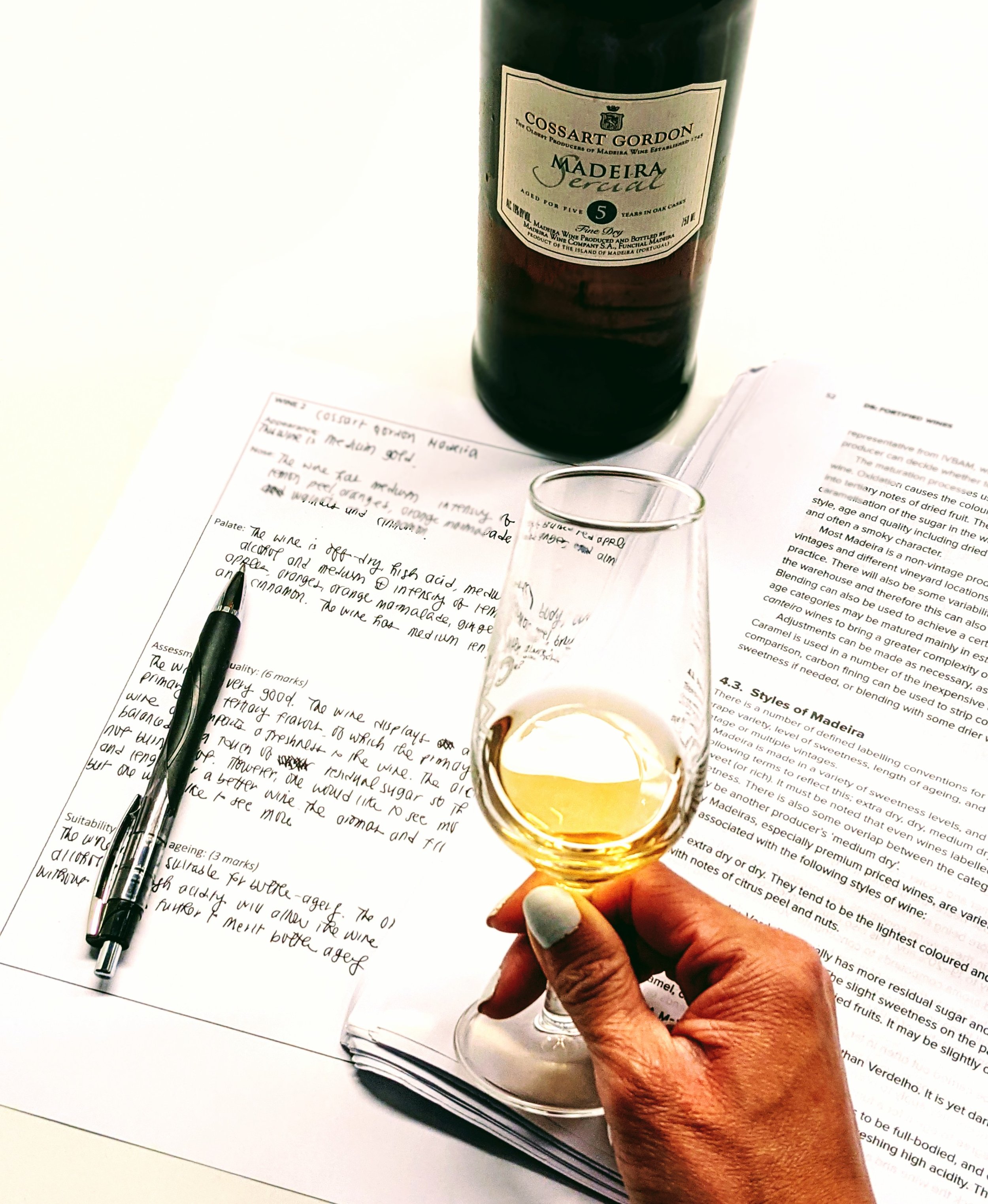

Examples of My Quality Assessments

A “good” Fino Sherry:

“This is a good wine. The wine displays concentrated medium+ aromas of green apple, hay, green olives and saline, which reflect the typicity of this style of wine. The low alcohol balances the concentration of the flavors, does not stick out of the wine and is well-integrated into the wine. The wine, however, falls short of being a very good wine because it lacks staying power on the palate with a medium- finish, and the wine does not have any additional complexity of interesting flavors beyond the typical ones expected of this style of wine.”

A “very good” Ribera del Duero Reserva (Tempranillo):

“This is a very good wine. The wine displays a complex range of black fruit aromas (blackberry, blueberry), pencil lead and graphite, alongside aromas of sweet tobacco, cedar, smoke and vanilla. The aromas are specific and readily identifiable, and the secondary aromas do not overpower the primary fruit aromas. The medium+ acidity provides lift and freshness to the wine, and the medium+ tannins provide structure against the dense black fruit aromas. The wine would be an outstanding wine if it had a longer than a medium length and if the grippy tannins were slightly more integrated into the wine.”

An “outstanding” Brut Vintage Champagne of over 10+ years:

“This is an outstanding wine. The wine displays concentrated, pronounced aromas of ripe baked fruits (yellow apple, pear, lemon meringue), brioche, bread dough, toast, cinnamon, nutmeg, mushroom and hazelnuts. The primary, secondary and tertiary flavors balance each other out, with no one component overpowering the other categories, and the flavors unfurl on the palate with the long, layered finish expected of an outstanding wine. The high acidity brings lightness and freshness to balance out the tertiary flavors and the residual sugar in this off-dry wine. Finally, the wine’s creamy and persistent mousse is consistent with that of an outstanding sparkling wine.”

Practice, Practice, Practice

This sounds like a trite piece of advice, but how often do you sit down to practice and write the full quality assessment? Do you write them only when the instructor makes you write them in class? Do you write them only when you are with your tasting group?

Caroline told our class that when she was preparing for the Diploma exams, she wrote sheets of “dry” quality assessments (i.e., without a wine sample to taste along with). Writing tasting notes without wine??? Drinking and smelling is the fun part! However, if you really want to improve your tasting notes, you have to practice, practice, practice.

Sometimes, people say to me, “Oh, you write good quality assessments because you are a lawyer,” and it irks me a bit because it dismisses how much time I put into practicing them. Lawyers do not have a monopoly on critical thinking, and taking Caroline’s advice, I also wrote a lot of “dry” quality assessments until I started feeling like they were becoming second-nature to me.

I hear people often say that their quality assessments sound awkward and disjointed. However, they never bother to go back to fix them after they are done writing them the first time. Write some quality assessments untimed and write and re-write assessments for the same wine until you feel like it would receive a high score on the exam. Then write and re-write assessments for the next few wines until you are happy with them. After a while, you will start feeling like you know how you like to begin and close your quality assessments, you will discover your own cadence and writing style and you will be able to recall readily the things to consider in the quality assessment.

Everyone loves being a critic. It is the reason that there are so many wine Instagram accounts out there assigning scores or points to wines. However, being able to articulate well why a wine is of a certain quality takes skill and like any other skill, requires practice to improve. I too used to hate the quality assessment, but once I started pretending that I was a wine critic writing for Decanter or Wine Enthusiast while I was practicing them, it actually started becoming fun to me.

As one famous wine lover, Sir Winston Churchill, once said, “Difficulties mastered are opportunities won.”

Do you have any other suggestions for how to tackle the quality assessment for other Diploma candidates? Any thoughts on the advice above? Comment below!

Disclaimer: The advice contained in this article is derived purely from my personal opinions and observations. WSET has not reviewed or vetted this article.